“The COVID-19 Pandemic did not take place” – The role of hype and an autobiographic reflection on COVID-19 communication strategies

Drawing on autoethnographic reflection and media theory, this blog explores how hype, attention economies, and digital sociality reshaped public engagement and trust during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Italy, March to May 2020. Full lockdown. Isolation, distance-learning, and remote working shaped daily life, while the health crisis was mediated almost entirely through screens: images and sounds of sirens, rising death tolls, seemingly without respite.

I soon found myself - a social science researcher with a training in media studies - reflecting on the role of official and unofficial communication online throughout the pandemic, asking myself how hype shapes public engagement throughout the pandemic, and how media literacy influences the way people navigated the COVID-19 “infodemic”.

I started looking for answers to these questions by analysing and interpreting cultural and social meanings through some of my personal experiences, which is what scholars also refer to as autoethnography. This was useful to better understand what has been happening, and why, since the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020, and gave me a chance to reflect on where I stand as both a researcher and a participant in family WhatsApp groups where disinformation about COVID-19 circulated in the early stages of the pandemic. By placing myself within the same digital environments I analysed, I acknowledged both my capacity to debunk misinformation and my limited influence in convincing others.

Analysing social media experiences with the help of theory

Much of my thinking here is shaped by an interest in the dynamics of the attention economy and parasocial relationships online, especially how social media platforms prioritise in terms of visibility and emotion, facilitating what people engage with and believe during moments of crisis.

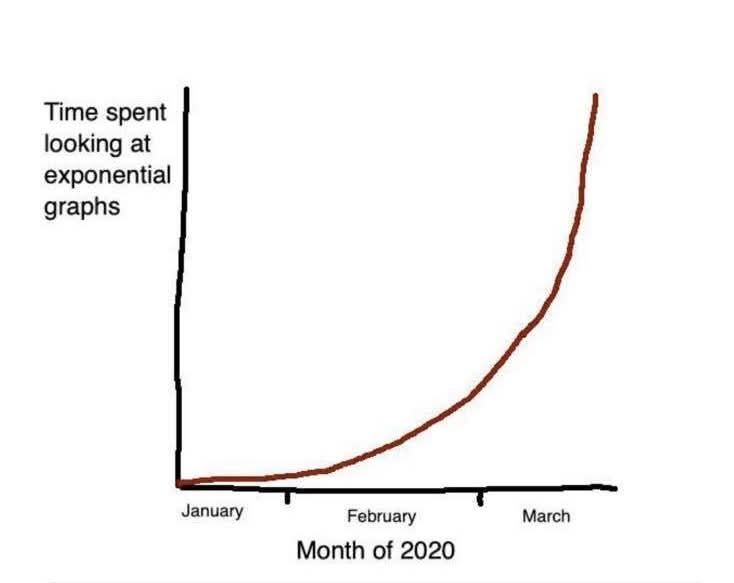

Baudrillard’s idea of the hyperreal helps explain how the pandemic became a mediated spectacle. With more memes, images, and symbolic content than epidemiological explanation, COVID-19 was often experienced less as a biological event and more as a stream of emotionally charged signs. These didn’t just represent the pandemic; for many, they became the pandemic by shaping how it felt and what it meant.

Bourdieu’s concept of social capital illustrates why some of these signs travelled further than others. In an infodemic, credibility rarely comes from institutions alone, but from trust embedded in social and parasocial networks made of friends, family, content creators, influencers: voices that feel familiar and emotionally resonant. This is where memes become important: they sit at the intersection of hyperreality and social capital, compressing complex realities into shareable, affective forms that move quickly through trusted networks, whether to cope, persuade, and sometimes mislead.

Then, both meme cultures and fake news dissemination rely on what could be called parasocial capital: the ability to mobilise attention, trust, and emotional responses at scale. But this same infrastructure could also be repurposed, if strategically engaged, to become tools for more effective and trusted health communication.

COVID-19 communication and social media

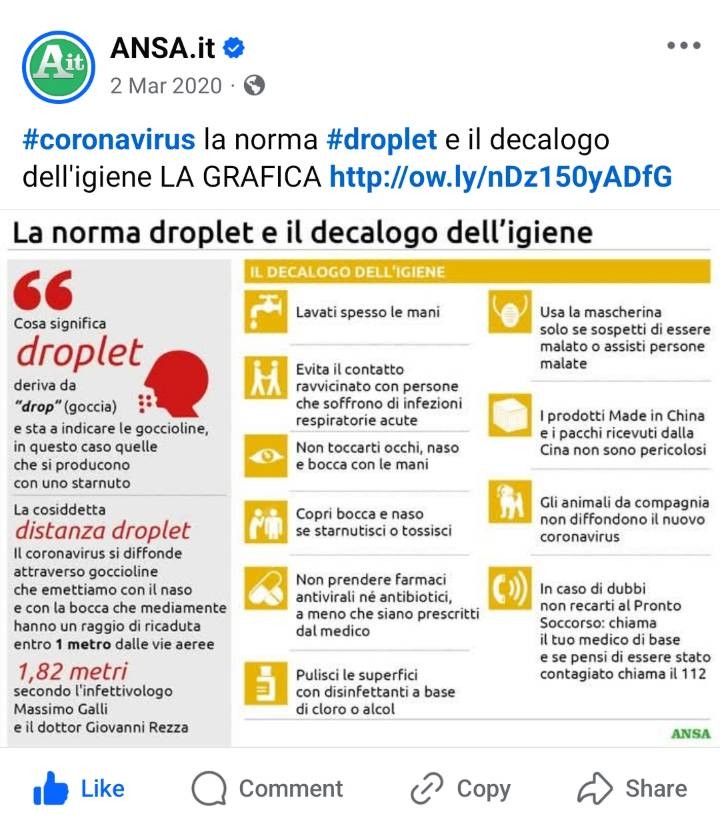

COVID-19 is likely going down in history as a global health and an institutional communication crisis; one where social media coverage and hype amplified and accelerated the spreading of misinformation. From its start, online communication about COVID-19 quickly evolved amid shifting health guidance and scientific uncertainty. Despite significant health communication efforts and a newfound sense of unity from most parties, key messages were often misunderstood, challenged, or reframed, eroding institutional trust.

Especially at the beginning, everyday communication relied heavily on WhatsApp chats, Instagram stories, tweets, where memes circulated as ways to cope, distract, or simply fill the silence. With social media amplifying this, it often prioritised emotional content to maximise user engagement, spreading disinformation through echo chambers.

This reality was bizarre, or thinking with Baudrillard, hyperreal. The pandemic became a mediated spectacle. With more images and memes about the pandemic and less content about its epidemiological complexity, we witness a collapse of the real into hyperreal, where representations become simulacra: signs that no longer point back to a stable reality but stand in for it. Were we reacting to the pandemic, or to the memes that referenced the pandemic? Images from the pandemic and memes did not merely represent events: for many, they became the experience itself.

Despite significant efforts, institutions failed to acknowledge uncertainty around a novel virus, and social media was inadequately employed by government agencies. This made room for content creators and influencers to shape how the pandemic was perceived, communicating information and giving advice themselves, with mixed results. This left the public to navigate evolving, sometimes contradictory public health advice within digital spaces optimised for speed and engagement rather than accuracy, fostering also science scepticism.

Instagram and Memes

My first autoethnographic reflection involved memes. I too created or shared them on social media and with my friends, as a way of coping with the fear and uncertainty dictated by the traumatic reality that was unfolding in front of our eyes and our screens.

The virus itself was invisible, memes weren't. Memes were a tangible form of media, offering emotionally resonant, easily shareable forms of meaning. The more time spent online seeking ways to cope, the more the memes themselves began to stand in for the pandemic. Amplified by hype and algorithmic visibility, they travelled faster and further than institutional explanations.

One can clearly see parallels to hype perceiving media as a spectacle that entertains people rather than giving them literacy to handle key phases of the pandemic. Audiences have long left behind the passive spectator role in favour of a more active one, serving as a catalyst. The pandemic helped us see that fandom culture in hype is sometimes more the driver - or trigger - of hype than the actual phenomenon. This was especially the case during early stages of the pandemic when the protagonist was the virus itself, an invisible but a menacing threat, and not yet the management of the global health crisis by governments and health organisations.

The virus has always been invisible, but in time the pandemic as a global health crisis became invisible too, drowned out by saturation. In this hyperreal space, emotionally charged signs replaced complex epidemiological realities, and in an attention economy, this emotional resonance was rewarded more than accuracy.

WhatsApp Disinformation

With friends, it's easier to curate the type of information you exchange with one another, while WhatsApp family groups do not always give you that choice. While in my family WhatsApp groups, I would often glance at fake news articles, videos, and voice notes that had been forwarded many times from other groups, including claims that migrants were immune to coronavirus, or that the virus had really existed since 2015.

For some of my loved ones, credibility and authority didn’t come from institutional sources, but from the trust in their social network, reflecting Bourdieu’s concept of social capital, even if the information received turned out to be false. These environments, which could have been used to better prepare for the health crisis ahead, instead fostered echo chambers where outsiders’ messages were met with scepticism, no matter how official.

Reflecting on this, I remember struggling with my ability to explain the pandemic to some of them, as it clashed with their reliance on peers, often highlighting an uneven distribution of media literacy by easily believing in news that fuelled racism, xenophobia, or offered easy fixes for a virus that just does not have one.

Health Communication in an Attention-Driven Environment

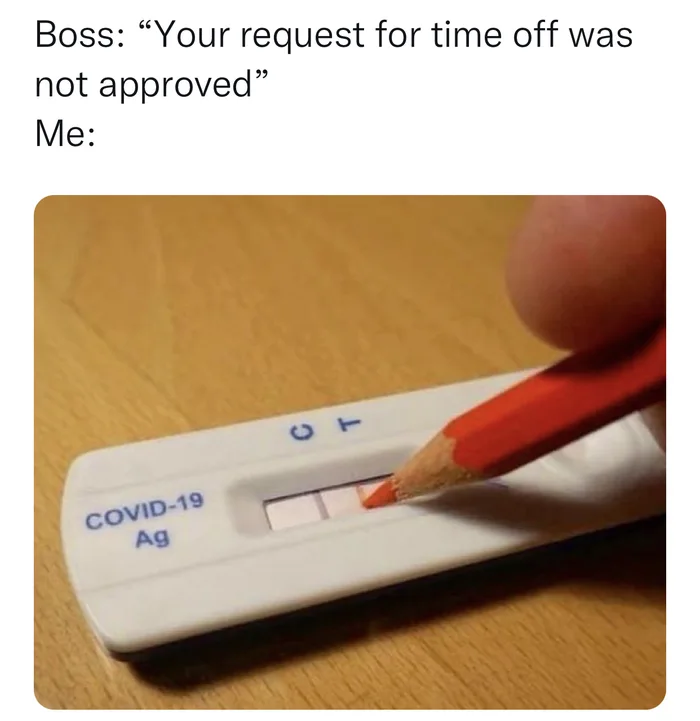

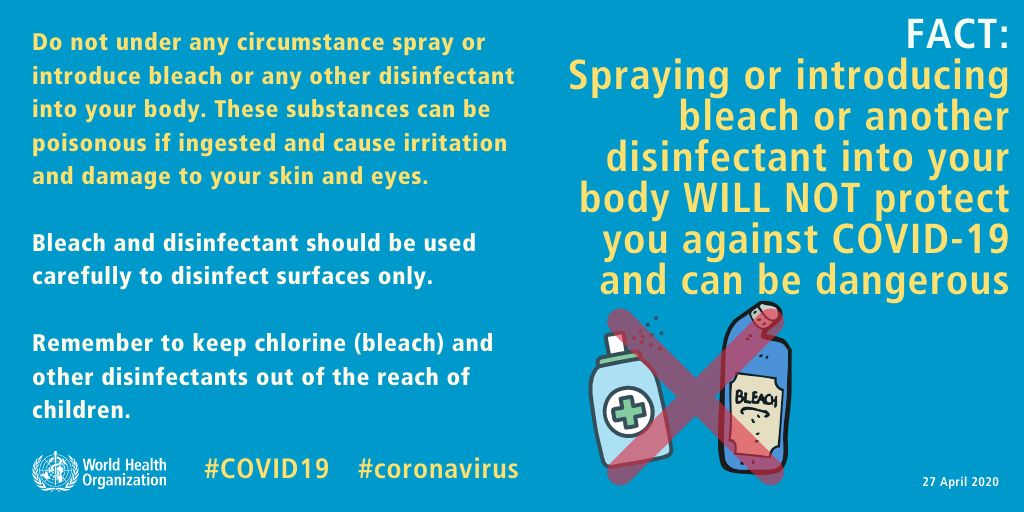

The WHO and Italian institutional communications about COVID-19 were generally accurate and carefully worded, but often long, and sometimes too complex to fully understand. Misleading and fake news, by contrast, looked appealing, were quick to ‘consume’, and offered a fix to a problem with no easy solutions.

However, the feelings of fear toward uncertainty and support from peer groups made it easier to believe them. The imbalance was stark: debunking disinformation required far more time and expertise than it took for fake news to go viral.

Communication Struggles

Science communicators and institutions faced multiple challenges. They needed to provide clear and frequent updates, often with uncertain, partial, or evolving information. Failing to acknowledge uncertainty early on left the general public unprepared for and sceptical towards changes in guidance.

How does all this translate to social media spaces? There, immediacy, affect, and algorithms dominate. The most emotionally resonant content won over the most factual; facts, however true (at the time of writing, with the current and limited knowledge at our disposal), were not as persuasive as, say, a storytelling approach, however false.

Parasocial relationships reigned: science communicators and medical professionals became influencers themselves, leaving behind their neutral position and positioning themselves to the left or to the right, supporting politicians who in turn often adopted a blame-oriented approach towards those questioning COVID-19 related guidance.

For example, the President of Campania De Luca, a region in Southern Italy, got angry with those wanting to organise graduation parties right at the end of the first lockdown, warning he’d send police armed with flamethrowers after them.

Hype-generating content at its best, but at what cost? Was this the right approach to dissuade those wanting to partake in one?

This kind of behaviour from an elected official would inevitably have consequences. Memes and reaction videos exploded, most agreeing with De Luca given the early stages of the pandemic, doubling down on those who had a desire to start to socialise in person again. This was done with little regard towards what would have happened when the roles inevitably reversed - people making fun of or threatening those who still wished to take precautions against viruses.

An inevitable outcome

Collapse of trust, mediated by hype.

Information overload and the trauma of lived experience led many people to disengage entirely with anything pandemic-related, while poor media literacy increased vulnerability to disinformation.

Even now, established facts about COVID-19 from early 2020 are being questioned. After a short period of collective shock and grief, the video of coffins transported by military convoys in Bergamo from March 2020 was suggested to be fake by some.

Institutional unpreparedness in the form of poor risk communication reinforced scepticism. Personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages in early 2020, requiring the general population to use whichever face-covering they could find (not necessarily the most effective), caused distrust towards the level of protection masks were providing, as the inertia towards explaining the efficacy of different types of face masks grew strong.

Between 2020 and 2021, the memes that circulated were critical of those who were not taking precautions against COVID-19; in later years, most memes made fun of those still taking precautions, as well as referring to the pandemic as something in the past. This was a shift partially dependent on social capital as, with time, more and more people would observe, trust, and follow what their social circles were doing, regardless of WHO or local governments' recommendations.

In the end, hype sustained attention on the pandemic as a topic, but it also eroded trust in official communication.

So, to conclude, did the pandemic “take place”? Of course, but for many it took place primarily as a media spectacle, mediated by hype. Even at the time of writing, the pandemic is still ongoing, as WHO continues to remind us in 2026, but who is paying attention anymore? Or rather, who – in 2026 – still believes COVID-19 is something worth paying attention to?

We are ill-prepared for communicating another global health crisis effectively. What can be done about it?

Perhaps, one of the first steps towards a better management of global health crises is to take advantage of hype, by leveraging parasocial relationship dynamics and strategically involve and train influencers to assist with part of the health communication work.

Secondly, institutions should - as a needed first step - better acknowledge uncertainty and complexity by creating more solid ground for science communication.

Then, there is a need for more widespread digital literacy; the general population should have more tools at their disposal to determine the reliability of sources, and to develop an understanding of how memes, humour, and emotionally charged content can subtly shape what feels true online, often more persuasively than formal news. This would perhaps in turn make us less dependent on social networks for truth.

And finally, trust must be rebuilt, as it is central to global health crisis management and a healthy functioning society.

I Giulia is an independent social researcher, motivated by understanding how digital media, trust, parasocial relationships, and attention economy dynamics shape people’s lives and interactions. I